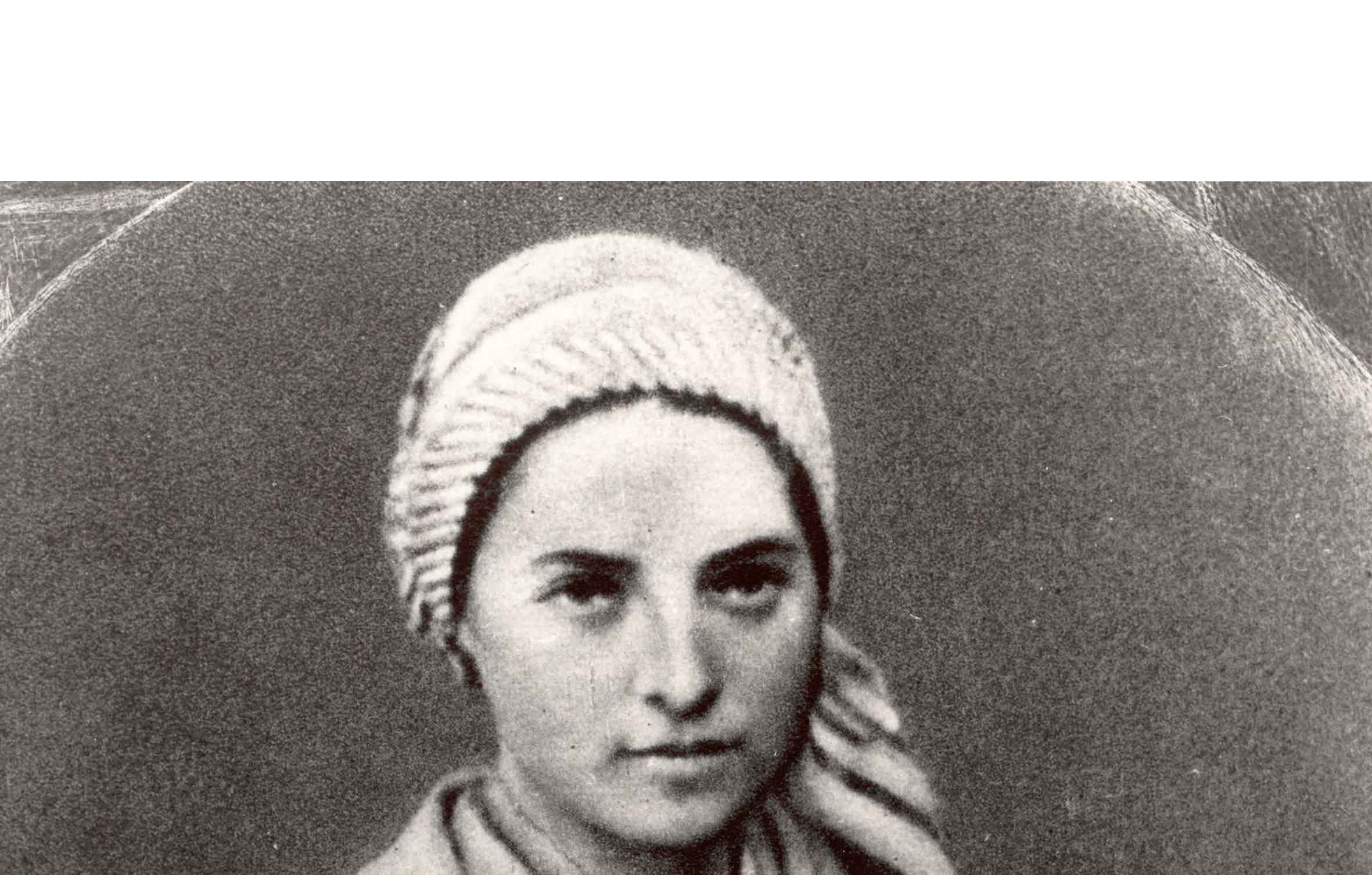

All that we know of the Apparitions and the Message of Lourdes came to us from Bernadette. She alone saw the Lady and all depends on her testimony. Who is she, then? Three periods can be distinguished in her life: the obscurity of her childhood, a “public” life at the time of the Apparitions and of giving testimony; finally, a “hidden” life as religious at Nevers.

Before the Apparitions

When one describes the Apparitions, Bernadette is often presented as a poor, frail and ignorant girl, living in miserable conditions in the Cachot. True, but it was not always thus. When she was born on 7th January, 1844, at the Boly Mill, she was the first child and heiress of Francois Soubirous and Louise Casterot who married for love. Bernadette grew up in a close-knit family in which she was cherished. Ten years of happiness in the decisive early years of her childhood made her strong and surprisingly balanced. The descent into the unhappiness which followed could not erase this human richness.

Bernadette, at 14 years of age, stood only 1 m. 40 tall. suffered from bouts of asthma. She had a lively, spontaneous and generous nature; she was witty and incapable of deception. She was proud, which didn’t escape Mother Vauzou in Nevers who described her as having“ a closed character, very touchy.” Bernadette’s faults distressed her and she fought them with energy. A strong personality but unsophisticated. No school for Bernadette: she had to help her aunt Bernarde. No catechism: her memory refused to retain the abstract phrases. At 14, she couldn’t read or write, and she suffered at being excluded. Then she reacted. In September 1857, she was sent to Bartrès. On 21st January, 1858, she returned to Lourdes. She wanted to make her First Communion. This she did on 3rd June, 1858.

The public life

This is how the Apparitions took place. In the midst of ordinary daily tasks, going to search for firewood, Bernadette was confronted by a mystery. A sound “like a gust of wind”, a light, a presence. Her reaction? She showed her common sense and a remarkable discernment. Believing herself mistaken, she used all her human resources: she looked, she blinked, she tried to understand. At last, she turned to her companions to check their impressions: “Did you see anything?” She turned then to God: she took up her rosary. She turned to the Church and took advice in confessing to Father Pomian: “I saw something white in the form of a Lady.” Questioned by the commissioner Jacomet, she replied with a confidence and prudence and a firmness which was surprising in a young uneducated girl: “Aquero, I didn’t say ‘the Holy Virgin’… Monsieur, you’ve changed it all.” She reported what she had seen with a detachment, an astonishing freedom: “I’m charged with telling you, not with making you believe.”

Her accounts of the Apparitions were precise, never adding or retracting anything. At one time, taken aback by the severity of Father Peyramale, she added a word: “Father, the Lady always asks for a chapel….even a very small one.” In his pastoral letter on the Apparitions, Mgr Laurence emphasized “the simplicity, the candour, the modesty of this child…she recounts it without affectation, with a touching innocence…and to all the questions put to her, without hesitation, she gave clear, precise responses, impressed with a strong conviction.” Unaffected both by threats and attempts to bribe her with advantageous offers, “Bernadette’s sincerity is irrefutable: she has not wanted to make a mistake.” “But has she herself been mistaken? Victim of an hallucination?” the bishop wondered. He recalled her calmness, her good sense, the absence in her of any exaltation and also the fact that the Apparitions did not depend on Bernadette. They happened without Bernadette expecting them, and in the fortnight, twice, when Bernadette went to the Grotto, the Lady was not there. Bernadette had to respond to the curious, to admirers, journalists and others, to appear before civil and religious commissions. She found herself thrown into the glare of the news; a “media storm” battered her. She needed patience and humour to stand firm in this storm and to preserve the purity of her testimony. She accepted no payment. “I want to remain poor.” She did not bless the rosaries thrust at her: “I don’t wear a stole.” She did not sell medals: “I’m not a merchant.” And faced with images of herself costing ten ‘sous’: “Ten ‘sous’, that’s all I’m worth!”

In these circumstances, life in the Cachot was no longer possible. It was necessary to protect Bernadette. Father Peyramale and the mayor Lacade were in agreement: Bernadette would be admitted as “a sick poor person” to the hospice managed by the Sisters of Nevers. She arrived there on 15th July, 1860. At 16, she learned to read and write. One can still see today, at the Bartres Church, the writing practice strokes she made. Later, she wrote often to her family and even to the Pope! She visited her parents who had been rehoused in the “paternal home”. She looked after the sick, but above all she was seeking her vocation: good for nothing and without a dowry, how was she to become a religious? At last, she joined the Sisters of Nevers “because they did not try to attract me.” From that time on, a truth impressed itself within her spirit: “My mission in Lourdes is finished.” Now, she had to withdraw in order to give all the space to Mary.

The hidden life at Nevers

She herself used this expression: “I came here to hide myself.” In Lourdes, she was Bernadette, the visionary. In Nevers, she became Sister Marie Bernard, who would be saint. One often hears about the severity of her superiors towards her, but it has to be understood that she was a unique case: she had to be shielded from curiosity, to be protected, and the community also had to be protected. Bernadette gave her account of the Apparitions before the assembled community on the day after she arrived; thereafter it was not to be spoken of. She was kept in the Mother House where she loved to care for the sick. On the day of her Profession, no particular office/work had been prepared for her: the bishop declared that her work would be “the work of prayer”. “Pray for sinners”, the Lady had said. She remained faithful to this. “My weapons,” she wrote to the Pope, “are prayer and sacrifice.”

Her own illness made her a regular patient in the infirmary, and then there were endless parlour visits. “These poor bishops, they’d do better to stay at home.” Lourdes was a long way off… she would never return to the Grotto. But every day she made her pilgrimage in spirit. She did not speak of Lourdes; she lived its message. “You will become the first to live the message,” said her confessor Father Douce to her. And in fact, after having been assistant infirmarian, she entered bit by bit into sickness herself. She did “her work” in this, accepting all crosses, for sinners, in an act of perfect love. “After all, they are our brothers.” During long sleepless nights, uniting herself with the Masses celebrated throughout the world, she offered herself as a “living crucified” in the tremendous combat between light and darkness, bound, with Mary, to the mystery of the redemption, eyes fixed on the crucifix: “That is where I find my strength.”

She died at Nevers on 16th April, 1879, aged 35. The Church proclaimed her a saint on 8th December , 1933, not for having been chosen for the Apparitions , but for the way in which she responded to that grace.